Engraving of Washington’s birthplace site, Source: NYPL

Since little is known of Washington’s childhood, myth has often shrouded reality. Contrary to popular opinion, the legend of the cherry tree incident appears to have occurred only in the mind of Parson Weems. Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “Washington is the last person you’d ever suspect of having been a young man.” Indeed, Washington’s legendary stature often detracts from our ability to understand his youth. Nathaniel Hawthorne humorously noted, “He had no nakedness, but was born with clothes on, and his hair powdered, and made a stately bow on his 1st appearance in the world.”

George Washington was born on February 11, 1732 around 10 a.m. at the family’s estate in Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in a scene probably nothing like that which Hawthorne described. It must be noted that at the time, the Julian calendar was still in use in the colonies and when Britain adopted the new Gregorian calendar, eleven days were added, moving Washington’s birthday to February 22nd. He was born to Augustine Washington, a Virginia planter, and Mary Ball Washington, a strong-willed woman who had been orphaned in her youth. She probably named young George after her guardian, George Eskridge. A recurring theme throughout Washington’s life would be his strained relationship with his tempestuous and controlling mother. Although young George had two older brothers from his father’s first marriage, Lawrence and Augustine, he was his mother’s oldest child. His parents would have four more children after George that lived to maturity.

Mary Washington, Source: Harper’s Encyclopedia of United States History, 1912

Washington is often inaccurately portrayed as having been born wealthy. Although his father owned large quantities of land, the Washington family was just outside the upper crust of Virginia’s elite class. Only through a combination of family marriage and George’s own efforts at self improvement did he achieve upward social mobility. Augustine’s business pursuits would lead him to move his family around the Potomac area in Virginia. George himself, unlike most of the founders, had an irregular education. By age eleven, young George had developed basic reading, writing, and mathematical skills with a particular aptitude in the latter. He was also a child of the outdoors, as he enjoyed riding, hunting, and other activities of the frontier.

Washington’s Augustine father passed away when he was eleven. His father had provided for his two eldest sons an education in England. Now that his father had passed, young George would not be afforded the same opportunity for a cosmopolitan education. As if to compensate for this misfortune, when George was fourteen, his older brother Lawrence arranged for him to become a midshipman in the British Navy. Washington’s mother, however, vetoed the idea. As disappointed as young George must have been, one can imagine the profound effect this had in history as it would have deprived the later American cause of its greatest leader.

Lawrence Washington

Young George’s brother Lawrence, who was fourteen years his senior, would serve as a mentor and father-figure. Lawrence had served in the British Navy during the War of Jenkins’ Ear, earned a royal commission, and was named adjutant general of Virginia. He also married into the Fairfaxes, one of Virginia’s most prominent and wealthy families. Young George idolized his brother Lawrence for his military and social success. The Fairfax clan would introduce George to the world of high society and provide him with opportunities crucial to his career. Young George began to adapt the manners of the Fairfaxes and the upper class. At the age of sixteen, he famously copied down the 110 The Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation, a Jesuit instructional guide on social etiquette, as an exercise in penmanship, but it is likely that he incorporated the rules in his conduct.

Young George Washington As A Surveyor, Source: Bettmann/CORBIS

That same year, George moved in with Lawrence’s family at their estate in Mount Vernon (named after Lawrence’s British commander). Around this time, to help his cash-strapped family, Washington began his first career as a surveyor. It was a perfect fit for his mathematical skills and love for the outdoors. In March of 1748, the Fairfax family sent Washington on a month-long surveying trip of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Shenandoah Valley. The following year, Washington’s excellent surveying abilities and the patronage of the Fairfaxes earned him an appointment as surveyor of Culpeper County, the youngest surveyor in Virginia history. Washington was already demonstrating an ability for efficiency and organization that was the hallmark of his career.

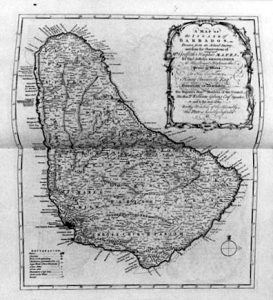

Map of Barbados, 1750

Soon, however, tragedy struck. Beginning in 1749, Lawrence had developed tuberculosis. By 1751, when George was nineteen and Lawrence was thirty-three, both men traveled to Barbados in a desperate attempt to revive Lawrence’s flagging health. It would be the only time Washington would ever venture outside the colonies. It was a brutal trip for Washington, as he contracted smallpox. Although the disease would leave Washington’s face scarred and pockmarked, and as some historians have speculated, sterile, it would immunize him from the disease – a fact of no small significance as disease would ravage his armies during the Revolutionary War. Lawrence Washington died back in Mount Vernon on July 26, 1752. Washington, at the age of twenty, had lost a father-figure once again. However, by this time Washington was a rising young figure in Virginia’s social and military circles.

Sally

Despite his manly physique, Washington was an awkward youth, especially with women. Illustrative of this fact was a clumsy poem he wrote around 1750: “From your bright sparkling Eyes, I was undone;/ Rays, you have more transparent than the sun/ A midst its glory in the rising Day/ None can you equal in your bright array..” Just before Washington wrote this doggerel that he met the alluring Sally Fairfax, falling deeply for her charms. Few subjects of Washington’s youth incite as much interest as this episode.

Sally Fairfax

Sally was a sensual beauty with a cosmopolitan air. She was well-educated, fluent in French, and trained in the social graces of the Virginia elite. She was also two years older than Washington, perhaps adding to her mystique. There was one problem: she was married to one of George Washington’s close friends, George William Fairfax. As Washington’s military career took off, he remained smitten and continued to indulge in a flirtation with her through correspondence. Sally appears to have both engaged in the flirtation while also keeping him at arms’ length. However Washington felt for her, his was a doomed loved, for the fact remained that she was a married woman and there was no conceivable way for him to pursue her.

By 1758, Washington was engaged in a whirlwind courtship with Martha Dandridge Custis, a woman who, while not possessing Sally’s sensual beauty, was a far better fit as a spouse. In September 1758, he wrote her a now-famous letter, obliquely confessing his feelings for her:

Tis true, I profess myself a votary of love. I acknowledge that a lady is in the case, and further I confess that this lady is known to you. Yes, Madame, as well as she is to one who is too sensible of her charms to deny the Power whose influence he feels and must ever submit to. I feel the force of her amiable beauties in the recollection of a thousand tender passages that I could wish to obliterate, till I am bid to revive them. But experience, alas! sadly reminds me how impossible this is, and evinces an opinion which I have long entertained, that there is a Destiny which has the control of our actions, not to be resisted by the strongest efforts of Human Nature.

Washington is partly evasive and partly revealing in the letter, but seems to have come to terms with the fact that his feelings for her were doomed. Soon after, Washington married Martha and they both remained close friends with George and Sally Fairfax. It must be conceded that George engaged in a dangerous flirtation with a married woman – something that shocks modern audiences given his reputation that he “could not tell a lie.” This was not his finest moment. However, the fact of the matter is that he never strayed from fidelity with Martha, despite the fact that both couples remained very close and frequently visited each other. In the end, Washington was able to control his youthful infatuation when it mattered most.

Perhaps things worked out better in the end. As the Revolution broke out, George and Sally Fairfax remained loyal subjects of the British King, moving to England in 1773, an irony since their old neighbor was now leading the American cause.