“Friends and Fellow-Citizens”

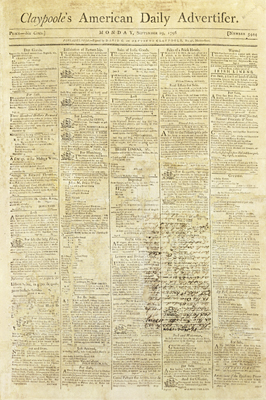

American Daily Advertiser, September 19, 1796, Source: The Gilder Lehrman Collection

On September 19, 1796, on the second page of the American Daily Advertiser, a message appeared that was addressed, “To the People of the United States.” The title of the message disclosed the stunning news that George Washington was stepping down from the presidency into retirement. In time, that document would take on its more famous name: “Washington’s Farewell Address.”

To readers, the news was profound: George Washington was leaving public life forever. Somehow, the nation that desperately called for his services again and again would have to survive without its “indispensable man.” The republic he helped to steer for almost a quarter of a century was now on its own. The document, however, did more than just announce George Washington’s retirement. The Farewell Address also provided America with a rich legacy of wisdom culled from a lifetime of public service. Washington had mined a career that spanned war and revolution for “some sentiments which are the result of much reflection.” Washington hoped that his thoughts would be regarded by his countrymen for their “solemn contemplation” and “frequent review.” Ultimately, the Farewell Address allowed Washington to exert lasting influence upon posterity beyond his retirement and death and would guide his beloved country on its path as a world power.

A Collaboration

Embedded within the Address itself are the passionate quarrels of America’s founding era. Washington was completing his second term in office, which was lowlighted by the most vicious attacks of his career. Opposition newspapers slandered him as a closet monarchist. Ferocious demonstrations had surrounded his residence lambasting his foreign policy. Political allies had turned against him and worked to undermine his presidency. Virtually all of the issues Washington addressed in his Farewell had exploded unto the political battlefield during his tenure as president. Thus, the Farewell Address provides a window into the heated political debates of the time.

Washington and Hamilton inaccurately being portrayed as editing the Address together, Source: Architect of the Capitol

Perhaps it is symbolic that the document was a haphazard collaboration between Washington and two leaders of the dueling factions of the time: Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. At the end of 1792, as Washington contemplated retirement, he asked his then-confidant, Congressman Madison, to draft a valedictory address and provide recommendations on the best possible method presentation. Although Washington shelved Madison’s draft and would go on to serve a second term, it is surprising how much Madison’s influence still pervades the final document. It was Madison who wrote about the importance of national unity and recommended that the document be published in mid-September in the newspapers, both of which Washington eventually heeded.

By 1796, Madison had fallen firmly out of Washington’s favor and into Jefferson’s Republican camp. Thus, Washington turned to his now, most trusted adviser Alexander Hamilton. Sending Hamilton the Madison draft, Washington asked for a revision of the document but also permitted Hamilton to create his own fresh paper. Hamilton complied, sending Washington a revision of Madison’s draft and his own new version. Washington, impressed, decided to work with the latter. Since Hamilton was the author of the document, some believed that the Farewell Address was more his work than Washington’s. However, historians have concluded that Washington was the chief architect of the speech and that Hamilton adhered to Washington’s vision.

.

“Some Sentiments..”

Union

Early design from 1782 of the Seal of the United States, a symbol of national unity, Source: NARA

Several strands of thought run through the Farewell Address. The first is Washington’s unequivocal endorsement of the strong, central government – the union – that he helped put in place. The union, Washington wrote, was “a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize.” Although today, the survival of the national government is hardly a consideration, at the time there were serious doubts that the union would continue and that it could maintain the allegiance of all Americans. The issue was fraught with controversy. Some in the nation viewed the federal government with profound suspicion, while others believed that needed to be stronger. Washington, for posterity, was firmly coming down on the side of the national government. He reminded his fellow countrymen that their independence was “the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts.”

Washington’s reasoning went as follows: “All the parts combined cannot fail to find in the united mass of means and efforts greater strength, greater resource, proportionably greater security from external danger..” To Washington, union was a matter of practical reality. In a world with predatory imperial powers, America had won its independence through a national union and needed that same union to survive.

Washington then sounded a warning against what he felt was the greatest domestic threat to the union. “The alternate domination of one faction over another,” he admonished, “sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism.” To Washington, faction was the antithesis of union as such groups sought to undermine the interests of the national whole. Even worse, Washington believed, factions would serve as vehicles for individuals to acquire “absolute power” for their “own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.” The lessons of the French Revolution were fresh in Washington’s mind.

Corresponding with Washington’s support for union was his insistence that the American Constitution be obeyed and “sacredly maintained.” The Constitution itself was the blueprint of the federal union. Washington had spent his entire presidency scrupulously adhering to the letter of the Constitution and believed that, for the nation to survive, it couldn’t approach the document with mere lukewarm support. Thus, the Constitution, he wrote, “is sacredly obligatory upon all.” He warned against insidious attacks against the document in the form of “alterations which will impair the energy of the system.”

Public Credit

Washington, who had helped to inaugurate the Hamiltonian system of finance, then advised the American people to “cherish public credit.” From his own experiences in war, when the states and the national government had failed miserably in supporting the army, he warned “that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it, avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt.” Like many in the founding era, Washington warned against “ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear.” Washington, in some ways, spoke from experience, as he and his fellow Virginia planters had lived with perpetual debt. Consistent with his support of the Hamiltonian plan, Washington insisted the necessity of taxes to pay down the debt. “To have revenue there must be taxes.. no taxes can be devised which are not more or less inconvenient and unpleasant.”

“Harmony with all…”

Washington then turned to the issue that threatened most to tear the nation apart – foreign policy. Throughout Washington’s second term, he worked tirelessly to steer America through Europe’s continental wars. Washington, although a military hero, had seen the realities of war. He had watched soldiers march barefoot leaving bloody footprints in the snow. He saw his troops ravaged by smallpox, starving to death. Washington knew the enormous cost of war and, thus, wished for his nation to enjoy lasting peace. “Cultivate peace and harmony with all,” Washington advised. This rule extended not only to a republic like France, but for all nations. “Just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated.”

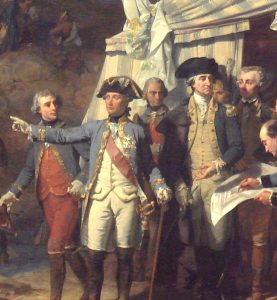

Washington with French Commander Rochambeau. French support was crucial during the Revolution. Source: Public Domain

During Washington’s presidency, the war between France and England put America in a dangerous situation, forcing it to choose between competing values. France was America’s indispensable ally in the War of Independence and was now in the throes of a republican revolution. It seemed to be a natural ideological fit with America – two republics marching together, side-by-side. On the other hand, America was highly dependent on British trade. To the consternation of many American supporters of the French Revolution, Washington instead issued a Proclamation of Neutrality. To some, Washington had betrayed the Revolutionary-era alliance with France. To make things worse, the Jay Treaty was seen as a kowtow to British tyranny. This was an easy charge to make, as the Jay Treaty was indeed heavily-stacked in Britain’s favor.

Washington, however, was no anglophile. His policy of Neutrality and support of the treaty rested purely with his political philosophy. Washington’s was a realist and understood the difficulty of establishing a republican government. He worried that France would erupt into anarchy and, eventually, tyranny. Additionally, republics exist in the real world, where balance-of-power politics reign and empires jostle violently for expansion. America, at the time, was an infant nation and was in no position to challenge the European superpowers. The best way for America’s republican experiment to survive, according to Washington, was to steer clear of any obligations or commitments that could entrap America into international conflicts. “It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Washington warned against “the insidious wiles of foreign influence” as the gravest threat to an independent foreign policy. Ideology, sentiment, and “passionate attachments” led to policies counter to the national interest and threatened American security.

It was not a romantic vision of American foreign policy but it was the one best calculated to ensure America’s survival. Washington was advocating prudence and moderation in calculating America’s interest. His vision would prove correct, as his hesitations about the French Revolution came to fruition. Even towards republics, America must act with caution and reason. France descended into anarchy and tyranny and Washington’s message of caution was vindicated.

Religion and Morality

George Washington portrayed praying at Valley Forge: Source: Public Domain

In discussing social issues, Washington upheld religion and morality as “indispensable supports” of a republican society and “great pillars of human happiness.” He maintained that religion could not be divorced from public and private morality. “Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.” To Washington, the fact that the Constitution forbade the establishment of a national religion did not preclude the crucial role that it should play in public life.

The issues of right and wrong, of justice and virtue, were not merely tools for social cohesion. Washington appealed to morality on multiple levels throughout the Address. He wished that public servants would conduct themselves in a manner so that the government’s administration would “be stamped with wisdom and virtue.” On the individual level, citizens as well as public servants “out to respect and cherish” religion and morality. This was because morality and religion were inextricably linked to “private and public felicity.” On the international and more transcendent level, Washington believed that the same obligations applied. Following the same reasoning on a larger scale, Washington wrote, “Can it be that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a nation with its virtue?” Thus, “Observe good faith and justice towards all nations.” Washington was appealing to the nation to act in an all “too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence.” In other words, our republic would be different not only in terms of structure but also in its virtuous conduct.

Washington ended on a humble note, stating “I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors.” Ultimately, Washington was challenging the American people to face the realities of a brutal world. Republican government, the most tenuous of all governments, required the best from its citizens: virtue, reason, and moderation. Indeed, no man in the world had a more profound understanding of the difficulties of establishing a republic.

Legacy

Upon its release, Washington’s Farewell Address was hailed as a sacred testimony by the nation’s founding father. Republicans, however, noted the veiled swipes Washington had leveled towards his opponents. The factions Washington spoke of undoubtedly were the Jeffersonians and Democratic-Republican groups that had opposed Washington’s policies. The “passionate attachment” Washington spoke of targeted the warm sentiments Republicans held for France. Madison himself criticized Washington’s veiled anti-French sentiments in the address and his “suspicion of all who are thought to sympathize with [the French] revolution.” The Farewell Address, however, would withstand the test of time and would be embraced as one of the defining documents of American political philosophy. In his old age, Madison described it as one of “the best guides to the distinctive principles.” Over a century later, Henry Cabot Lodge wrote, “no man ever left a nobler political testament.”

For years, the Farewell Address was memorized by young American schoolchildren and continues to be read annually in the U.S. Senate. Still, it remains a mysterious document that most Americans are aware of but few truly understand. Many have used the Address to justify isolationism, although the document is best described as supporting the philosophy of non-interventionism. Historians have ranked the document with the Declaration of Independence but few Americans can quote it verbatim. Unlike the Declaration or Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address or Kennedy’s first inaugural, the Farewell Address lacks soaring, inspiring rhetoric. Due to this disadvantageous comparison, the monumental significance of Washington’s valedictory is often overshadowed. However, unlike each of those documents, Washington’s Farewell had the greatest direct effect on national policy.

Washington’s advice became sacrosanct. His call for a perpetual union would be echoed by future presidents, most notably Andrew Jackson during the Nullification Crisis and Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. His call for an independent, interest-based foreign policy laid the foundation for the Monroe Doctrine and defined America’s posture to the world into the twentieth century. Even by 1949, when President Harry Truman took America into NATO, he had to contend with Washington’s warning against “permanent alliances.” By putting the weight of his prestige behind union and independence, Washington helped to keep America focused on the values that allowed its rise as a world power.