The Final Act

An aging George Washington painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1795, Source: Detroit Institute of Arts

Once again, in 1797, Washington stepped down from the pinnacle of power and retired as a private citizen. Although some had expected Washington to remain president for life, the publication of his Farewell Address in September 1796 marked his leaving the stage from public life for good. It was, perhaps, the most important act of his presidency and its reverberations would echo throughout American history. The Constitution, as written in 1787, had left open the possibility of a president-for-life who could be continuously re-elected without limit. Many Americans were understandably wary of this possibility and feared that future presidents could abuse their popularity into perpetual re-election. When Washington stepped down from office, he set an enduring precedent that became deeply woven into American political culture: that no president should serve more than two terms. Future presidents would honor Washington’s precedent for one hundred and fifty years until President Franklin D. Roosevelt won a third term in 1940. In 1951, the Twenty-Second Amendment to the Constitution enshrined Washington’s precedent into law, limiting all future presidents to two-terms.

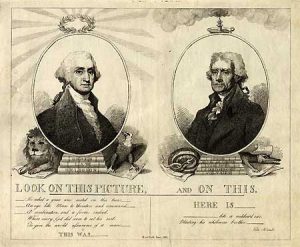

A pro-Federalist political cartoon favorably comparing Washington against rival Jefferson, 1807, Source: Political Cartoon Collection at the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts

Washington’s departure also heralded the first competitive presidential election in history. As a congressman put it, Washington’s retirement was “a signal, like dropping a hat, for the party racers to start.” Federalists rewarded the logical candidate, Vice President John Adams, for his loyalty to this Administration. Republicans rallied around their leader, former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Although both men were aloof to the campaign, it was a brutal contest as the lines drawn during the Washington Administration again rekindled their partisan fury. Although Washington had shed any pretense of bipartisanship and was firmly in the Federalist camp, he studiously remained neutral and determined to not interfere with the election (something many future presidents wouldn’t do). With commendable restraint, Washington set a high standard for political objectivity, respecting the people’s wishes in choosing their leaders. Vice President Adams eventually prevailed in the contest of 1796, narrowly defeating Jefferson, but due to a defect in the electoral system and mis-communication among Adams’ voters in the electoral college, Thomas Jefferson was elected as Vice President over Adams’ running-mate Thomas Pinckney. Despite their awkward relationship, Washington was certainly gratified that a Federalist was succeeding him to the presidency.

A young Andrew Jackson, future 7th President of the United States, Source: Heritage Auction Galleries

Washington delivered his final State of the Union address on December 7, 1796 at the House chamber in Philadelphia. Tears were shed in the gallery as Washington delivered one of his final public statements. Looking towards the future, he urged the creation of a national university, a military academy, and a naval force – each recommendation focusing on strengthening national unity and power. While his speech was well-received, a few congressmen, still incensed over Washington’s policy towards Britain, refused to join in Congress’s formal response. Among these individuals was a young representative from Tennessee, the future seventh president, Andrew Jackson.

The Rarest Moment in History

On March 4, 1797, Washington attended John Adams’ inauguration as the second president of the United States. The momentous event took place at the Hall of the House of Representatives in Federal Hall before a joint session of Congress. On stage sat the three great revolutionaries of America’s founding: George Washington, John Adams, the incoming president, and Thomas Jefferson, the incoming Vice President. For many, it was a moment of profound sadness for George Washington, after almost a quarter century of service as America’s preeminent leader, was leaving public life forever. Adams would later write that it was “the most affecting and overpowering scene I ever acted in.” It was also one of the rarest moments in history – a peaceful and orderly transition of power from one individual to another.

Adams, in his inaugural address, delivered a potent tribute to the man he, almost twenty-two years earlier when they were both young revolutionaries, had nominated to command the Continental Army. Adams lauded Washington as:

a citizen who, by a long course of great actions, regulated by prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude, conducting a people inspired with the same virtues and animated with the same ardent patriotism and love of liberty to independence and peace, to increasing wealth and unexampled prosperity, has merited the gratitude of his fellow-citizens, commanded the highest praises of foreign nations, and secured immortal glory with posterity.

In that retirement which is his voluntary choice may he long live to enjoy the delicious recollection of his services, the gratitude of mankind, the happy fruits of them to himself and the world, which are daily increasing, and that splendid prospect of the future fortunes of this country which is opening from year to year. His name may be still a rampart, and the knowledge that he lives a bulwark, against all open or secret enemies of his country’s peace.

After the address, as the three men were leaving the stage, Washington motioned for the new president and vice president to exit before him. It was a fitting gesture, symbolizing his new status as a citizen. Adams, in his usual self-conscious manner, noted Washington’s serenity. “I heard him think, ‘Ay! I am fairly out and you are fairly in! See which of us will be the happiest!’”

Moments later, Washington traveled to the Francis Hotel where President Adams had been staying. At that moment, a throng of well-wishers had gathered behind him. As he neared the hotel, Washington turned around to acknowledge the crowd, revealing tears streaming down his face. Those present at that moment would never forget the touching scene of their leader bidding his final farewell. “No man ever saw him so moved,” wrote an observer.

Amos Doolittle’s engraving of Washington as the symbol of national unity and civilian leadership, surrounded by the seals of the United States and the thirteen individual states, Source: Library of Congress