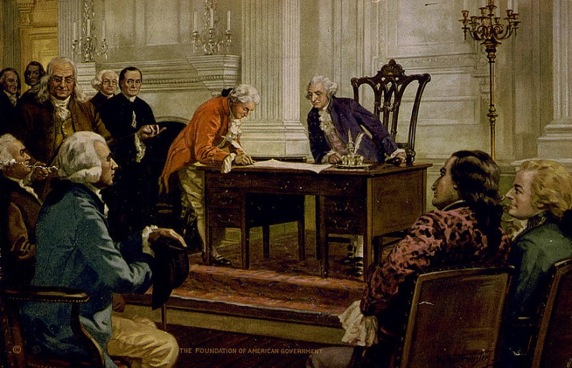

Henry Hintermeister portrait of the Constitutional Convention, showing Madison in the lower left and Washington presiding, Source: Library of Congress

Like Hamilton, Madison had shared Washington’s views on a strong central government in the aftermath of the war and became Washington’s most trusted adviser in the early years of his presidency. To Washington, Madison was an unrivaled authority on the Constitution and political philosophy. Regardless, these two Virginia planters, formed an odd pair. Whereas Washington was a majestic man of action, Madison was fragile and bookish in appearance. Their collaboration also bore much critical fruit for the young republic. Together they worked together to push through the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the foundational pieces of legislation during Washington’s presidency. However, as Madison became closer to Jefferson political persuasion, his relationship with Washington suffered. Like Jefferson, Madison was unable to maintain his friendship with Washington through the political wars of the 1790s.

Madison, in his retirement, wrote the following on Washington:

“The strength of his character lay in his integrity, his love of justice, his fortitude, the soundness of his judgment, and his remarkable prudence to which he joined an elevated sense of patriotic duty, and a reliance on the enlightened & impartial world as the tribunal by which a lasting sentence on his career would be pronounced. Nor was he without the advantage of a Stature & figure, which however insignificant when separated from greatness of character do not fail when combined with it to aid the attraction. But what particularly distinguished him, was a modest dignity which at once commanded the highest respect, and inspired the purest attachment. Although not idolizing public opinion, no man could be more attentive to the means of ascertaining it. In comparing the candidates for office, he was particularly inquisitive as to their standing with the public and the opinion entertained of them by men of public weight. On important questions to be decided by him, he spared no pains to gain information from all quarters; freely asking from all whom he held in esteem, and who were intimate with him, a free communication of their sentiments, receiving with great attention the different arguments and opinions offered to him, and making up his own judgment with all the leisure that was permitted. If any erroneous changes took place in his views of persons and public affairs near the close of his life as has been insinuated, they may probably be accounted for by circumstances which threw him into an exclusive communication with men of one party, who took advantage of his retired situation to make impressions unfavorable to their opponents.”