Neutrality

Washington receiving Citizen Genêt, Source: Library of Congress

By 1792, Europe was engulfed with conflict as France’s imperial neighbors feared the spread of revolution. Britain and France were officially at war by February 1793. This immediately created a crisis within Washington’s administration, pitting America between the two belligerents. Washington sought to maintain neutrality, a difficult task given Republican support for France and American economic dependence on Britain. At the same time, the new French ambassador Edmond-Charles Genêt, known as Citizen Genêt, arrived on American shores in April 1793, putting America in a bind. Washington sought the advice from his cabinet on whether to issue a neutrality proclamation and whether to receive Citizen Genet (or risk angering the British). Washington, seeking a middle way and taking advice from all sides of the spectrum, ended up siding with Hamilton in issuing proclamation and siding with Jefferson in receiving Genêt. The Proclamation of Neutrality, signed on April 22, 1793, became a pillar of American foreign policy for decades.

Unfortunately, Genêt had little respect for the proclamation and sought to circumvent Washington’s authority and enlist American popular support for France. Genêt proceeded to provoke rabid, pro-French mobs and demonstrations, some outside of Washington’s executive mansion, support the French practice of capturing British ships and outfitting them as privateers, and sponsored pro-French Democratic-Republican Societies. Jefferson continued to express enthusiasm for the French Revolution and warmly welcomed Genêt’s arrival. This put him in an awkward position as he stood in stark contrast with the Washington Administration’s growing concern that Genêt’s was provoking a possible American war with Britain. Throughout this time, Jefferson and Madison continued to covertly sponsor attacks on Washington’s policies, including his Neutrality Proclamation. In July 1793, Jefferson reported his intention to resign but Washington, hoping to keep ideological diversity, prevailed on him to postpone his retirement. In August of 1793, Genêt’s insulting attempt to circumvent Washington was made public, sparking outrage, and the cabinet unanimously requested France for his recall. Ironically, due to upheavals back in France, Genêt was now charged with crimes and ordered to stand trial, and Washington magnanimously secured his asylum in the United States.

The Jay Treaty

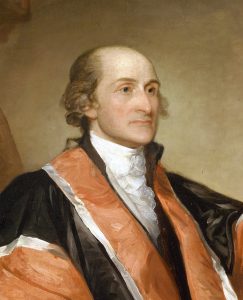

John Jay by Gilbert Stuart, Source: The National Gallery of Art

Great Britain remained a problem for Washington as well. By 1793 the British were seizing American ships, impressing sailors into the Royal Navy, and blockading the French West Indies from American commerce. War with with Britain loomed ever greater. In order to mitigate this threat, Washington decided to send Chief Justice Jay to negotiate a treaty with Britain and Jay sailed off in May 1794. After months of negotiations, in March of 1795 the treaty arrived. The document, in many ways, reflected the weak stature of the United States in the global balance of power. The British took advantage what little leverage Jay had, resulting in a treaty that granted Britain most-favored nation status in American commerce and obligated the United States to pay all prewar debts. The British practice of impressment remained unaddressed as were American claims for runaway slaves. The only major concessions the Americans received were a promise to vacate all Western forts, the opening of the West Indies to U.S. commerce, and compensation for unlawful confiscation at sea.

Washington himself was aghast at the meager benefits of the treaty. The overriding benefit of the treaty, however, went beyond what was enumerated in the document. The fact of the matter was that it kept the peace with Britain, buying precious time for the young republic to grow and mature. Once again, Washington was in a fix that gave the appearance that his government was much more sympathetic to Britain and not as “neutral” as it claimed to be. Washington sought to keep the treaty secret during the Senate debate for as long as possible in order to forestall the expected outcry. Washington himself maintained misgivings about the treaty and turned to the now-retired Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton ultimately urged the president to sign the treaty, which Washington determined to do.

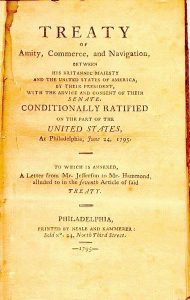

The Jay Treaty, Source: Library of Congress

Prior to the signing of the treaty, in July, the opposition paper Aurora, leaked the text of treaty to an outraged American public. Critics immediately targeted Jay, burning him in effigy and accusing him reducing the United States to pre-revolutionary servility to the British crown. Washington’s desk was besieged with resolution upon resolution castigating the document and urging its veto. Again Jefferson and Madison led the opposition, the former from his home in Monticello, and the latter in the Congress. Despite intense opposition, Washington’s prestige effectively carried the treaty and with Hamilton’s support, it barely passed Senate with the required two-thirds majority in August. Washington signed document soon thereafter.

Despite the document’s ratification, Republicans in the House still staged a last attempt to prevent it from being funded. House leaders argued that it too had a constitutional role in treaty-making, given its budgetary and commerce powers, and also demanded that Washington submit additional related documents to Jay’s treaty. Washington again turned to Hamilton for advice, who advised him to resist the House’s attempt to take down the ratified document. Washington himself believed that this was a dangerous encroachment by the House upon the exclusive constitutional powers of the president and the Senate. In the end, Washington’s prestige again carried the day and the House backed down from its challenge. Since the bruising debate pitted Washington against his former confidant James Madison, both remained estranged afterward. Nevertheless, the president’s treaty-making powers were secure and the nation would avoid war.

Political cartoon depicting Jefferson attempting to slow Washington’s move towards the Federalist party, Source: the New-York Historical Society