Foreign Policy Precedents

Washington’s residence in New York City, 1789-90, Source: NYPL

Throughout Washington’s presidency, a number of critical decisions would define the relationship between the executive and legislative branches in the realm of foreign policy. Although the Constitution had divided up foreign policy and war-making powers between the president and the Congress, the president’s powers were more vague and their relationship had yet to be fleshed out. Perhaps the most well-known incident in this early relationship occurred during a visit Washington paid to the Senate in August of 1789 seeking approval for a three-man commission to negotiate a treaty with the Creek Indians. The Constitution stipulated that treaties and appointments made by the president required the “advice and consent” of the Senate. Washington intended to adhere to the letter of the Constitution and hoped for the Senate to play a significant advisory role, perhaps a grander version of his war councils from his days as commander of the Continental Army. Also, the fact that the Senate was considered the more prestigious of the two branches appealed to Washington’s preference for elite, disinterested public servants.

Washington’s visit was a disaster. Vice President Adams’ reading of the treaty could scarcely be heard by the senators. Soon the senators requested that Washington provide supporting documents related the treaty so they could be referred to a committee. Washington was infuriated, muttering “This defeats every purpose of my coming here.” It was the last time Washington would appear before the Senate. To Washington, it became clear that obtaining the “advice and consent” of the Senate would simply be impractical and could subject future American foreign policy crises to endless debate and the executive branch to endless scrutiny. Indeed, during Washington’s term, the Congress challenged the president’s power to fire appointees without Senate consent. Washington’s visit and his reaction set a critical precedent, establishing for the executive branch significant discretion and making it the primary actor in the realm of foreign policy.

Revolution

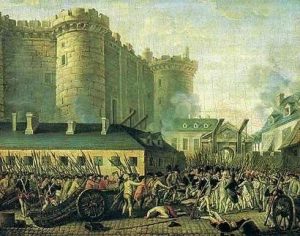

Throughout 1789, France was in major upheaval. In the spring and summer of that year, the National Assembly was organized and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen were written by Washington’s dear friend Lafayette (with assistance from Washington’s future Secretary of State Jefferson). By October, outright revolution had broken out with the storming of the Bastille. The French Revolution would increase the growing divide between the two developing American parties, the Federalists and Republicans, as each side viewed the outcome central to the survival of the republic.

The Storming of the Bastille, Source: Public Domain

Republicans and a significant segment of Americans recalled with gratitude the French alliance during the Revolutionary War that was indispensable to American victory (the economic cost of which laid the foundation for the French Revolution itself). Additionally, personal ties to the French revolutionaries (many of whom, like Lafayette, had served in America) and their republican ideology inclined Americans towards supporting the French against the British, a common enemy. While sentiment appeared to favor support for the French cause, it was simply a fact that American commerce was overwhelmingly dependent on British trade. Herein rested the central dilemma of early American foreign policy.

Washington himself expressed high hopes for the events in France, but viewed the international scene from a purely realist perspective. Washington remained cautious, fearing that the excesses of the French Revolution would turn violent – an assessment that would prove correct. Also, America itself was a fragile republic, encircled by the British, French, and Spanish colonial powers who were in league with and instigated various Native Americans tribes at the American borders. A second war with Britain remained a distinct possibility as they continued to ignore many of the Treaty of Paris’ stipulations, such as the evacuation of western posts. Washington, in his first year as president, hoped to mitigate this threat by improving relations with Britain. Also, he believed that the common language, culture, and religion that Britain and America shared made these two former adversaries natural allies. Towards this end, Washington sent Gouvernor Morris as an unofficial envoy and permitted Hamilton to serve as a back channel. Hamilton’s meetings with British diplomat George Beckwith were crucial in turning British sentiment towards warmer relations with America, resulting in the appointment of George Hammond as the first British ambassador to the former colonies in 1791.

Jefferson vs. Hamilton

Washington’s residence in Philadelphia, Source: Watson, Annals of Philadelphia (1830)

The great tragedy of George Washington’s foreign policy is that there was simply no way for him to avoid charges of being pro-British. Washington’s own views were much more nuanced than his detractors would admit, but neither the Federalists nor the Republicans were given much to nuance. The struggles over assumption, the bank, and the French Revolution increased the chasm between the two growing political parties, led by Washington’s top deputies, Hamilton and Jefferson. Federalists viewed Republicans as closet Jacobins, hoping to export the French revolution in the United States and spread anarchy all over the land. Republicans viewed Federalists as closet monarchists, hoping to plant the corrupt royal system and submit the nation once again to pre-independence status under the crown. Indeed, there were Federalists and Republicans on each side at the extremes. Hamilton himself had dangerously mused about the benefits of monarchy and a life-long president, and he was an unbridled admirer of the British system. Jefferson and his Republicans understandably feared Hamilton’s more extreme tendencies, but unfortunately, in their attacks, they did not distinguish between High Federalists like Hamilton and others like Washington who, in his nature, was more predisposed to objectivity and moderation.

Although accused as Hamilton’s puppet, Washington was in complete control of his administration. He had supported Hamilton’s domestic program because it had lined up with many of the views he had had since his days as commander. Additionally, Washington was no closet British admirer, having suffered through decades of disillusion with the British going back to his being denied a commission as a royal officer. Washington believed in warming relations with the British less out of sentimental attachment or bias and more out of a realist assessment of American foreign policy interests. However, in an age when newspapers raged on both sides about the extremist tendencies of the opposition, this posture appeared to many Republicans as monarchical and pro-British. Washington, throughout his administration, would remain stuck in the cross-hairs of this debate.

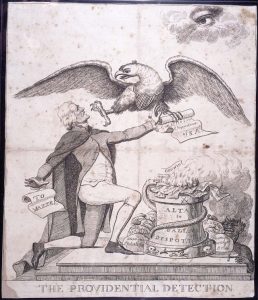

Political cartoon attacking Jefferson, Source: American Antiquarian Society

Throughout the rest of Washington’s first term, the attacks between Hamilton and Jefferson would become more and more severe. Although Washington tried to remain above the fray, it was clear that his own views inclined more towards Hamilton’s. Newspapers and gazettes became the central battlefield of this conflict. In 1791 Jefferson hired Philip Freneau in the State Department on a sinecure that permitted him to serve as editor for the pro-Republican paper The National Gazette, a response to the pro-Federalist Gazette of the United States. Hamilton often attacked the Republicans under a pseudonym in the latter paper, and Freneau could now respond in kind. That year, Madison himself wrote an anonymous attack on the Washington Administration.

In modern times, it is difficult to imagine a sitting member of the cabinet orchestrating attacks against the incumbent president’s administration, but that is exactly what happened in Washington’s presidency. Yet, during his first term Washington was not fully informed on the source of the attacks and still placed a great deal of trust on Jefferson and Madison. Both Jefferson and Madison found themselves in the awkward position of criticizing an immensely popular president’s policies (whom Jefferson served) without attacking him directly. Thus, their attacks focused primarily on Hamilton, but with an implicit charge that Washington himself was being manipulated.

Throughout it all, Washington sought in vain to reconcile his two brilliant feuding officers. He hoped that “wounding suspicious and irritating charges [would give way to] mutual forbearances and temporary yieldings on all sides.” The attacks wounded him and put him on the defensive regarding his administration’s policies, but he earnestly wished to keep an ideological balance in his government.