By 1775, Colonel George Washington was a veteran of the French and Indian War, a wealthy landowner, a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and a delegate to the Continental Congress. As Britain and her American colonies edged towards confrontation, Washington had emerged as a leader in the colonial cause and was zealously organizing a military defense. The crucial step in his career, however, took place in Philadelphia on June 15, 1775 when fiery Massachusetts delegate John Adams rose to nominate George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the newly-proclaimed Continental Army. In a gesture of endearing modesty, Washington darted out of the room as Adams spoke, as if he was humbled by his nomination. The next day, the delegates voted unanimously to appoint Washington, one of their own, to the position. Instantly, Washington’s stature was transformed; in one moment, the provincial gentleman from Virginia became the premier symbol in the cause of liberty.

In a sense, Washington was the only real choice. Colonial America had few men with military experience to turn to. Also, Adams’ nomination was a shrewd one: he hoped to unify the delegates behind what was largely a New England cause and Virginia was the largest of the colonies. Securing Virginia’s support was crucial for the military effort going on around Boston. However, Washington’s own modesty, dignity, and martial presence (he had worn his military uniform to the sessions) had earned the admiration of the delegates. Also, he was among the few leaders in colonial America to have any semblance of military experience. It seemed that destiny was calling Washington to the grandest of stages.

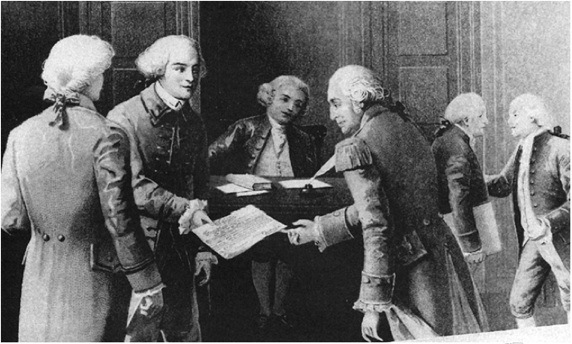

Washington leaves the room as John Adams nominates him as commander-in-chief, Source: Library of Congress

The enormity of the task momentarily overwhelmed the now-General Washington. On his shoulders rested the hopes of his fellow countrymen and the destiny of generations. As he accepted his commission, he admitted, “Though I am truly sensible by the high honor done me in this appointment, yet I feel great distress from a consciousness that my abilities and my military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important trust… this day declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.” In another gesture of modesty, Washington eschewed the offer of a salary and required only that his expenses be covered.

Shortly thereafter, General Washington traveled to Boston to take command of his army. He had never commanded an army in battle before. He arrived at Cambridge on July 2, 1775 to the sight of a bedraggled, undermanned, underfed, and under-supplied army. Disease was festering all around the camps due to unsanitary conditions. History had given this Virginia planter the task of molding this mass of humanity into a fighting force that could defeat the most powerful nation in the world.

Washington receives his commission, Source: Library of Congress